Deadlock in International Joint Ventures: A Design Failure, Not a Legal Problem

Why governance design matters for decision-making in international joint ventures.

Deadlock in international joint ventures is often treated as a legal contingency, something to be resolved through arbitration clauses, buy-sell mechanisms, or judicial intervention once relations deteriorate. This framing is convenient, but it is largely mistaken. In practice, deadlock is rarely an unexpected disruption. It is usually the predictable outcome of governance and decision-making structures adopted at the formation stage.

Understanding deadlock as a design failure rather than a legal problem shifts attention to the choices parties make long before disputes arise. It also explains why legal remedies, however carefully drafted, frequently arrive too late to preserve the venture’s commercial purpose.

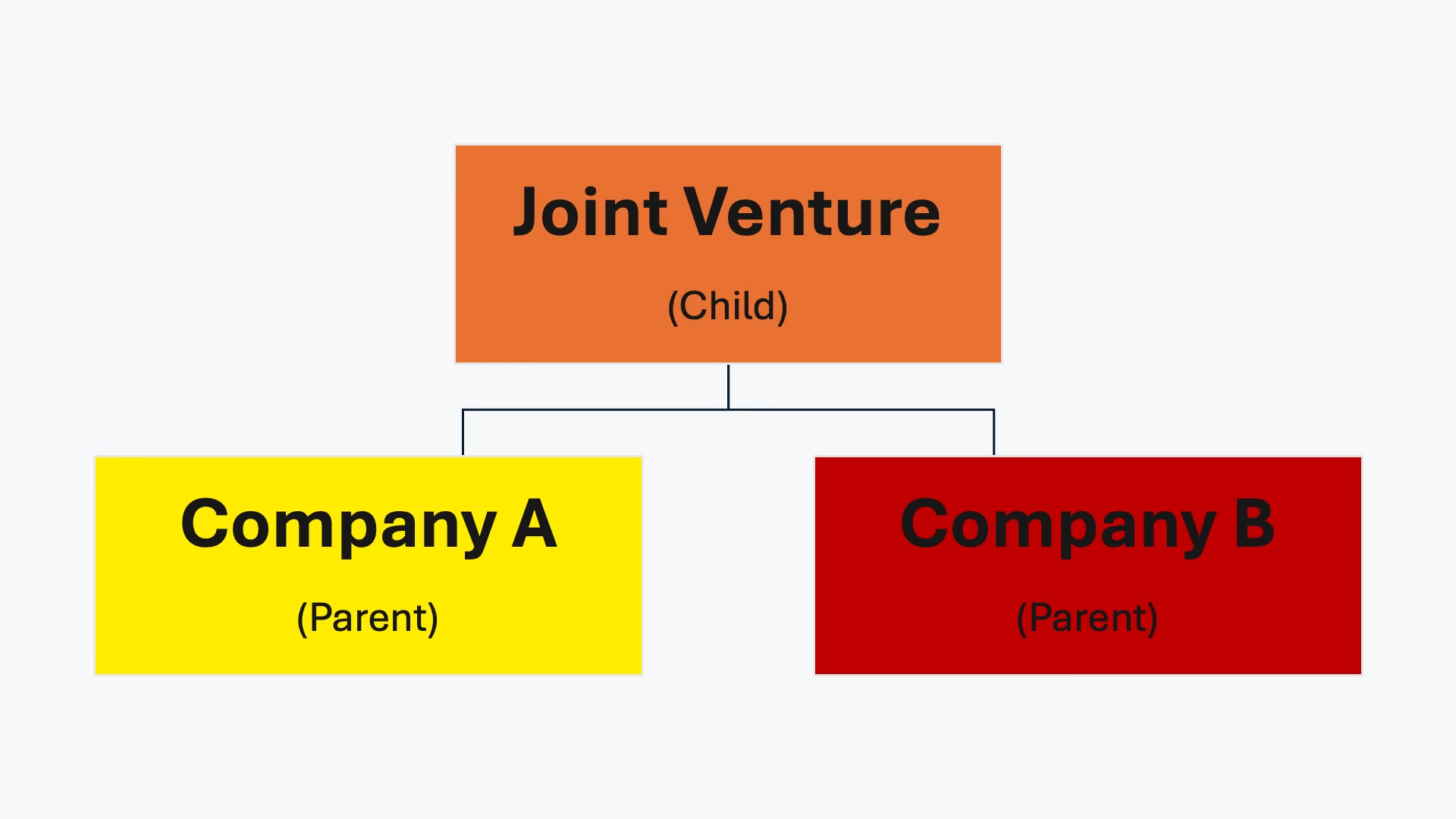

Deadlock in international joint ventures is rarely an unexpected disruption. It is usually the predictable outcome of governance and decision-making structures adopted at the formation stage. For foundational context, see our article on what international joint ventures are and how they are structured.

What Deadlock Looks Like in Practice

Deadlock does not usually present as open conflict. More often, it appears as paralysis. Board meetings produce no decision. Strategic initiatives stall. Capital contributions are delayed. Managers defer responsibility upward, only to find that the governing body lacks mechanism to resolve disagreement.

In international joint ventures, this paralysis is often masked by procedural formality. Meetings continue. Minutes are taken. Committees are convened. Yet no party has the authority or incentive to move the venture forward unilaterally. Over time, operational inefficiencies harden into strategic drift, and the joint venture ceases to function as an integrated enterprise.

How Deadlock is Designed at Formation

Most deadlock scenarios can be traced to governance choices made at the outset of the joint venture. The most common source is symmetry without hierarchy. Equal ownership, equal board representation, and expansive veto rights are frequently adopted in the name of fairness. In reality, they often eliminate the possibility of decisive action.

Reserved matters and unanimity requirements further exacerbate this problem. While intended to protect minority interests or preserve strategic balance, overly broad veto rights can convert ordinary business decisions into bargaining chips. When every meaningful decision requires consensus, disagreement becomes structurally consequential rather than episodic.

Symmetry without hierarchy often eliminates the possibility of decisive action. This structural issue is explored further in our discussion of joint ventures types and ownership design.

Importantly, these features are not accidental. They are often the product of negotiations focused on risk avoidance rather than operational functionality. Parties concentrate on preventing worst-case outcomes, such as loss of control, unfavorable dilution, or unilateral strategic shifts, without equal attention to how the venture will actually make decisions under stress.

Why Legal Mechanisms Rarely Solve Deadlock

Joint venture agreements often include mechanisms intended to address deadlock, including escalation clauses, buy-sell provisions, or arbitration triggers. While these tools have a role, they are reactive by nature. They do not restore effective governance but only provide an exit or adjudicative pathway once governance has already failed.

Legal mechanisms manage consequences, but they do not cure the underlying structural defect. For related analysis, see our article on cultural considerations in dispute resolution clauses.

Moreover, invoking these mechanisms is financially and strategically costly. Formal dispute resolution shifts the relationship from collaboration to adversarial positioning. Even when resolution is achieved, the joint venture itself is often damaged beyond repair. This is why deadlock is rarely “solved” in a meaningful sense. Legal mechanisms manage consequences but they do not cure the underlying structural defect.

The Cultural Overlay: Authority, Consensus, and Silence

In cross-border joint ventures, governance design interacts with cultural expectations in ways that intensify deadlock risk. Different legal and business cultures hold fundamentally different assumptions about authority, consensus, and escalation.

In some context, authority is expected to be exercised clearly and hierarchically. In others, decision-making is relational and consensus-driven. When governance structures assume one model while participants operate under another, formal equality can conceal substantive confusion.

Silence is particularly dangerous in this setting. What appears to be agreement or acquiescence to one party may signal discomfort or resistance to another. Without clear decision rules and escalation pathways that account for these differences, cultural misalignment becomes embedded in the venture’s governance architecture.

Deadlock as a Symptom of Strategic Misalignment

Deadlock is also frequently a signal that the parties’ strategic objectives have diverged. Joint ventures are often formed around overlapping but not identical goals, including market access, technology sharing, risk allocation, or regulatory positioning. Over time, these priorities evolve.

When governance structures lack flexibility or clarity, strategic divergence manifests as decision paralysis. Parties may no longer disagree openly about objectives, but their inability to agree on execution reveals a deeper misalignment. In this sense, deadlock is less a discrete event than a symptom of structural incoherence.

Designing for Decision, Not Just Protection

Preventing deadlock requires a shift in emphasis at the formation stage. Rather than asking only how to protect against adverse outcomes, parties must also ask how decisions will be made when interests diverge. This does not require abandoning safeguards or minority protections. It requires calibrating them. Clear allocation of decision rights, narrowly tailored reserved matters, and defined escalation authority can preserve balance while maintaining functionality. Most importantly, governance design must reflect how the venture is expected to operate in practice rather than how it should be protected in theory.

Conclusion

Deadlock is international joint ventures is the foreseeable result of governance structures that prioritize symmetry over decision-making and protection over functionality. Treating deadlock as a legal problem obscures its true origin and delays meaningful intervention. When understood as a design failure, deadlock becomes predictable and preventable. The challenge for parties is to design governance structures capable of sustaining decision-making under real commercial and cultural pressures.